Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

Tom Garing cleans up racist graffiti painted on the side of a mosque in what officials are calling an apparent hate crime, Wednesday, Feb. 1, 2017, in Roseville, Calif. (AP Photo/Rich Pedroncelli)

Many people were concerned about President Donald Trump's response to the New Zealand mosque shooting in March, when he seemed to downplay the seriousness of white nationalism.

Sen. Amy Klobuchar, D-Minn., in an interview with CNN’s Jake Tapper, criticized Trump’s rhetoric for dividing people. She noted that the Christchurch shooter said that Trump was a symbol of "renewed white identity."

Tapper cited the upward trend of hate crimes in many parts of the world and highlighted the rise of white nationalism in the United States. "There has been an increase in hate crimes," Klobuchar agreed. "There has been an increase in very negative rhetoric at groups."

When we looked at hate crime statistics in the United States, we found that while hate crimes reported to the police did go up in recent years, the full picture is more nuanced.

Here, we'll examine in both police data and survey estimates to explain the trend of hate crimes. (We're not putting Klobuchar's comments on our meter because her statement was vague and didn't specifiy a timeframe.)

Police data has shown recent uptick of total hate crimes

Hate crimes are defined as "crimes that manifest evidence of prejudice based on race, gender or gender identity, religion, disability, sexual orientation, or ethnicity," according to the Hate Crime Statistics Act passed by Congress in 1990.

Hate crimes can be committed against people, property or society, and can include violent attacks, robbery, as well as arson and vandalism.

The FBI reported 7,175 incidents of hate crimes in 2017 (the most recent data available). The number of offenses presents a 17 percent increase from 2016, and an uptick for three consecutive years from 5,479 incidents in 2014.

FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting program aggregates voluntary reporting data from law enforcement agencies nationwide and identifies those offenses that constitute hate crimes. The growth of hate crimes from 2016 to 2017 coincides with the drop in overall violent crimes, robbery and property crimes, meaning that the crimes resulted from biases account for a more significant percentage of crimes overall.

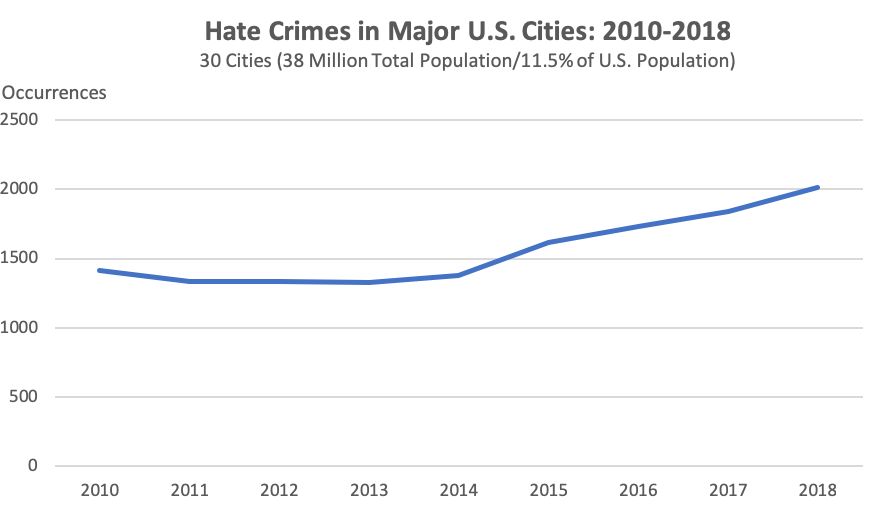

Crime researcher Brian Levin, the director of Center for the Study of Hate & Extremism at California State University, surveyed official local police data from 30 large American cities in 2018 and found that "this is the first time in this decade that collection of cities has hit 2,000... and has its steepest increase since 2015."

Source: Kevin Grisham and Brian Levin of the Center for the Study of Hate & Extremism-California State University, San Bernardino

Looking at cities individually, 70 percent of the cities reported an increase from 2017 to 2018, and slightly less than half hit a decade high, Levin said. The cities that recorded decade-high hate crimes include Los Angeles, Chicago, Houston, Philadelphia, Dallas, Austin, San Francisco, Fort Worth, Seattle, Washington, D.C., Louisville, Sacramento, Miami, New Orleans, and Cleveland.

However, Levin said that some of the increase, especially in cities with very low numbers before, was the result of the more rigorous reporting.

Emeritus professor at Carnegie Mellon University Alfred Blumstein said with the increasing national attention, people could be more ready to report hate crimes to the police and are better equipped to decide if an offense is a hate crime when targeted to members of a special group.

Survey data indicates declining unreported victimizations

Both data collected by Levin and FBI has a caveat — they contain the reported crimes only. The Bureau of Justice Statistics, however, reports a much larger number of hate crimes, typically over 20,000 from 2009 to 2017. Instead of using police data, the agency conducted the National Crime Victimization Survey and counted unreported offenses where hate languages and symbols were present.

Data from the newest BJS hate crimes statistics briefing — different from the FBI data — shows that there’s a significant decrease of hate crimes overall from 2014 to 2017, plunging 25% in 2015, and staying almost flat under 20,000 from 2015 to 2017 (the annual total is calculated with a three-year-average for each year and rounded to the nearest hundreds).

The analyses of victimization numbers done by Barbara Oudekerk, a statistician at BJS, indicate that reported incidents, which are often reflected in the FBI data, have increased, while unreported incidents decreased by 40 percent from 2014 to 2017.

An earlier BJS study concluded that there was no statistically significant change in the annual rate of violent hate crime victimization from 2004 to 2015, and the raw numbers of total victimization decreased.

Hate crimes directed to them because of their gender and disability account for 27% and 16%, respectively, of the hate crimes identified by victims in the survey from 2013 to 2017, according to the briefing. In the same period, however, neither category of hate crimes identified by law enforcement exceed 2 percent of the total, according to UCR data.

Hate crimes go unreported for many reasons: Many victims couldn't cite tangible evidence of hate to be used by the police; some Latinos were afraid of deportations if they report; LGBTQ people sometimes don't report because of distrust in the police, a News21 investigation found.

This set of survey data has the limitation that it does not include crimes against organizations and relies on sampling.

Finally, there is also some truth to Klobuchar’s statement about the adverse effects of negative rhetoric. After studying the pattern and seasonality in the FBI data, the Center for the Study of Hate & Extremism found that "hate crimes have increased in every presidential election year since national FBI recordkeeping began in the early 1990s." In 2016, the spike also corresponded with the election month of November.

Levin said that hate crimes fluctuate more than usual around "catalytic, emotionally-charged events, terrorist attacks, and conflictual elections."

"We’ve seen that hate crimes have increased not only around all elections, but Brexit as well in the UK. That’s a lesson for all of us to maybe tone down the rhetoric," Levin said.

Our Sources

CNN, Klobuchar on NZ: Trump's rhetoric "doesn't help", March 17, 2019

The New York Times, Massacre Suspect Traveled the World but Lived on the Internet, March 15, 2019

FBI: UCR, 2017 Hate Crime Statistics, 2016 Hate Crime Statistics, 2015 Hate Crime Statistics, 2014 Hate Crime Statistics, 2013 Hate Crime Statistics 2012 Hate Crime Statistics, About Hate Crime Statistics, Accessed March 20, 2019

Bureau of Justice Statistics, Hate Crime Statistics, 2009-2017, March 29, 2019

Bureau of Justice Statistics, Hate Crime Victimization, 2004-2015, June 2017

Center for Public Integrity, Millions are victims of hate crimes, though many never reported them, August 16, 2018

The Hill, Tweet about Amy Klobuchar’s speech at the Human Rights Campaign, March 15, 2019

Email interview with Brian Levin, director of Center for the Study of Hate & Extremism-California State University, San Bernardino, March 21, 2019

Email interview with Tannyr Watkins, public affairs specialist at Department of Justice, April 1, 2019

Phone interview with Brian Levin, director of Center for the Study of Hate & Extremism-California State University, San Bernardino, March 20, 2019

Email interview with Alfred Blumstein, emeritus professor of urban systems and operations research at Carnegie Mellon University, March 21, 2019

ADL, Murder and Extremism in the United States in 2018, Accessed March 20, 2019

National Police Foundation, Releasing Open Data on Hate Crimes: A Best Practices Guide for Law Enforcement Agencies, Accessed March 26, 2019

The Washington Post, Trump says white nationalism is not a rising threat after New Zealand attacks: ‘It’s a small group of people’ , March 15, 2019

Center for the Study of Hate & Extremism, Hate Crimes Rise In U.S. Cities And Counties In Time Of Division & Foreign Interference, May 2018

OSCE, ODIHR Hate Crime Reporting, United States, Accessed March 19, 2019

PolitiFact, Donald Trump doesn’t think white nationalism is on the rise. Data show otherwise, March 20, 2019

PolitiFact Rating:

PolitiFact Rating: