Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

People are using coronavirus-related code words in their social media posts to try to evade content moderators that look for misinformation about COVID-19.

If Your Time is short

-

Social media users are employing coded language, such as deliberate misspellings and symbols, to try to evade detection by platforms seeking to contain the spread of COVID-19 misinformation.

-

Social media platforms have flagged and removed some posts that spread misinformation. But other posts have escaped moderation.

-

The use of code words can help connect and build trust with a community of like-minded users who can decipher them, but complex codes can also confuse people, limiting the potential reach of misinformation among those who can’t.

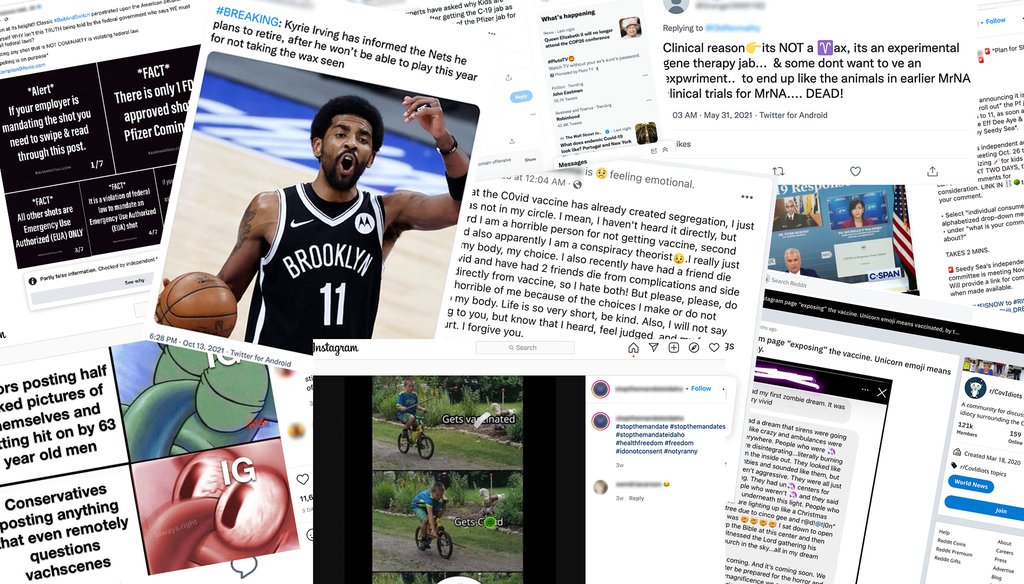

"Vaccine" shows up in social media posts as "vachscene" or "wax seen." "COVID-19" is spelled with zeros instead of O’s, or trimmed to "C-19." The CDC and the FDA on Instagram become the "Seedy Sea" and the "Eff Dee Aye."

Are people on social media really such awful spellers?

Not in these cases. They’re using intentional misspellings and other linguistic tricks to evade detection from content moderators and algorithms that scour social media posts for possible misinformation related to COVID-19.

The codes can be more cryptic than mere misspellings and wordplay. There are anti-vaccination Facebook groups named "Dance Party" and "Dinner Party," NBC News reports, and Instagram users are dubbing vaccinated people "swimmers."

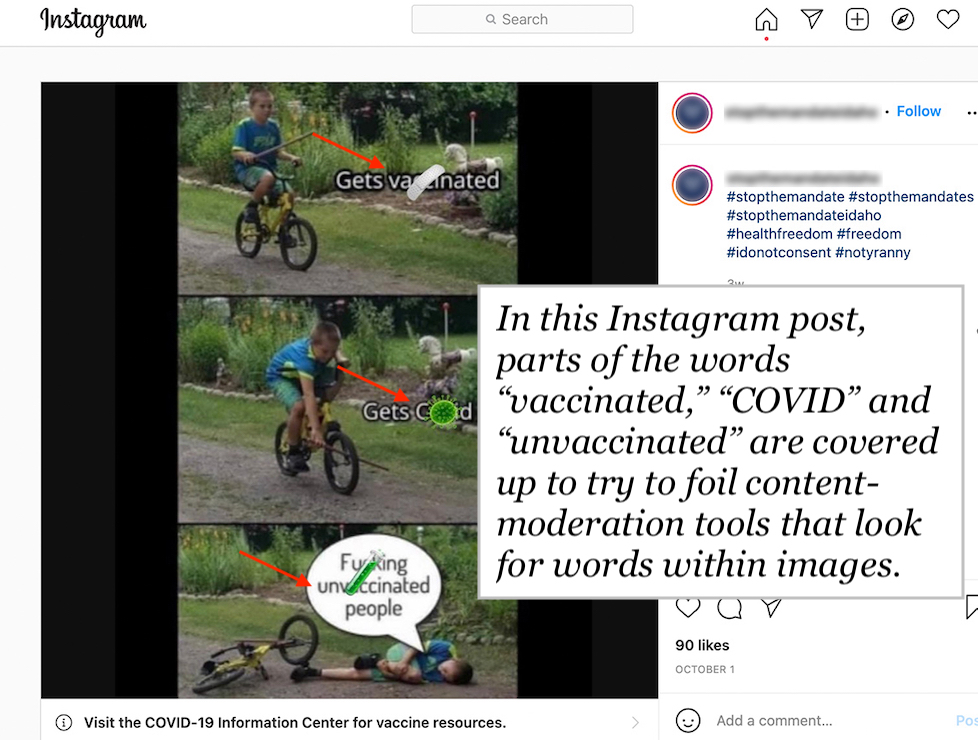

There are visual tactics, too. An Instagram post, for example, covers up parts of the words "vaccinated," "COVID" and "unvaccinated" in the image to try to flummox content-moderation software that picks words out of images. Another post, reshared on Reddit, uses a unicorn emoji as a stand-in for vaccines. A Twitter post swaps the "V" in "vax" with the V-shaped symbol for the zodiac sign Aries (♈).

The evasion tactics can make social media posts read like Mad Libs or a rebus puzzle. To people who are sticklers for spelling or confused by odd syntax, they might be a clear sign that the post should be viewed with skepticism. But to like-minded users, these codes may signal that they are included in a kind of secret society, with its own beliefs and dialect.

"The coded language is effective in that it creates this sense of community," said Rachel Moran, a researcher who studies COVID-19 misinformation at the University of Washington. People who grasp that a unicorn emoji means "vaccination" and that "swimmers" are vaccinated people are part of an "in" group. They might identify with or trust misinformation more, said Moran, because it’s coming from someone who is also in that "in" group.

Can social media platforms and their misinformation detectors recognize this coded language for what it is?

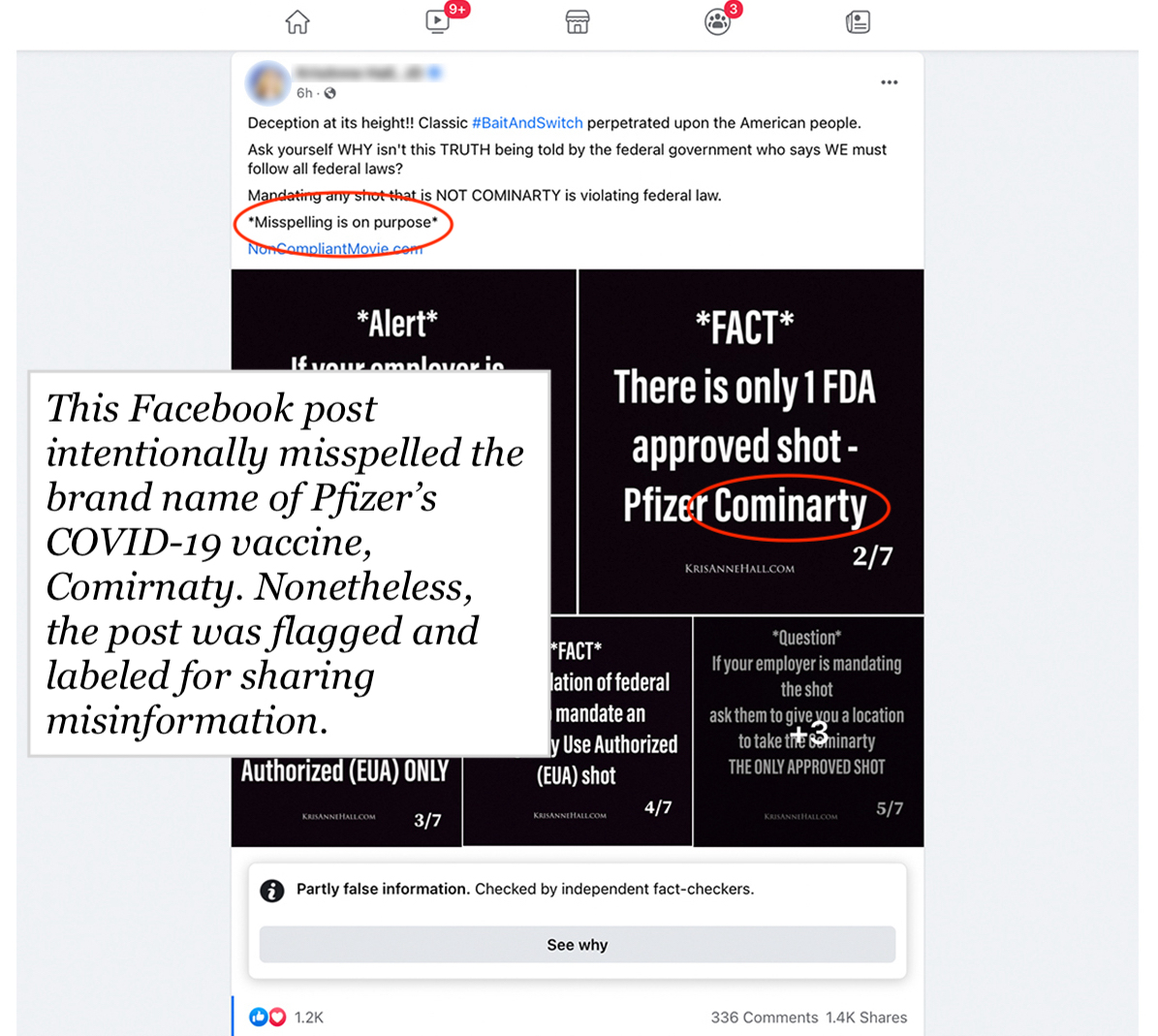

Sometimes. Some posts with coded language and false information do get snared and labeled or removed. For example, Facebook flagged and PolitiFact fact-checked a post that intentionally misspelled Comirnaty, the brand name of Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine, as "Cominarty." Facebook added a "partly false information" banner to that post with the fact-check because it contained inaccurate information about vaccine mandates.

But other posts with more elaborate codes continue to elude detection and spread misinformation. And social media users keep inventing new spellings, phrases and visuals to try to outsmart platforms’ moderation efforts and prevent their posts from being flagged with a misinformation label. Users also try to prevent a link to Facebook’s COVID-19 information page from showing up on their coronavirus-related posts.

The Instagram user who tried the spelling "vachscenes" in an Oct. 19 post added a caption saying, "Let’s see if my horrific misspelling of that word prevents that sticker from popping up on the bottom of my post." As of Oct. 27, there was no sticker. (The post doesn’t make a fact-checkable claim, so it didn’t get a fact-check.)

Platforms say their enforcement is working

Twitter said in an email to PolitiFact that it tries to catch the codes through its automated detection systems, powered by machine learning. And it said it’s continuously trying to improve its detection methods to keep up with new coded language tactics. After PolitiFact mentioned the misspelling of COVID-19 with a zero instead of an "O," Twitter said it was working to incorporate "c0vid" into its detection streams.

Facebook, for its part, said the appearance of coded language is a sign that its content-moderation systems are working.

"This is exactly what happens when you are enforcing policies against COVID misinformation — people try to find ways to work around those restrictions," a Facebook spokesperson told PolitiFact in a statement.

Facebook partners with more than 80 fact-checking organizations around the world, including PolitiFact, to fact-check posts suspected of sharing misinformation. It has removed 20 million pieces of COVID-19 misinformation and labeled more than 190 million pieces of COVID-19 content rated by its fact-checking partners, the spokesperson told PolitiFact.

Nonetheless, said Moran, the misinformation researcher, efforts to penalize users for spreading misinformation have backfired. If an Instagram user’s account is taken down, "that’s almost worn as a badge of honor," she said.

"You become a kind of martyr for the cause," Moran said. "So when you make your backup account or your second account, people will immediately go follow it because you have that certain credibility from being censored."

Is coded language effective at spreading misinformation?

Moran said the codes themselves may end up limiting the reach of misinformation. As they get more cryptic, they become harder to understand. If people are baffled by a unicorn emoji in a post about COVID-19, they might miss or dismiss the misinformation.

"There’s definitely drawbacks when you add codes," said Moran. "They minimize, maybe, the reach of misinformation."

In a way, "that’s hopeful," she added, "because we’re hoping to stem the tide of misinformation and avoid it being spread so widely that it becomes part of mainstream conversation."

On the other hand, she said, the codes actually might serve to embed misinformation more deeply in those people who are already vaccine-hesitant or vaccine-opposed "because it speaks to them directly and their knowledge bases."

Moran said it’s hard to get people out of the "in" group. "It’s less about the information itself, and it’s more about the social aspect of being involved with something," she said. "And that's really something that’s hard to fact-check someone out of."

RELATED: CDC is not manipulating its COVID-19 breakthrough data — it’s changing how it collects it

RELATED: No, the COVID-19 vaccines are not weapons of mass destruction

RELATED: False vaccine claims persist on Facebook, despite a ban. Here’s why

Our Sources

Email from Twitter to PolitiFact, Oct. 26, 2021

Email statement from Facebook to PolitiFact, Oct. 26, 2021

Zoom interview with Rachel Moran of the Information School at the University of Washington, Oct. 22, 2021

NBC News, Anti-vaccine groups changing into 'dance parties' on Facebook to avoid detection, July 21, 2021

Facebook, How Facebook’s third-party fact-checking program works, June 1, 2021

Twitter, COVID-19 misleading information policy, accessed Oct. 25, 2021

Virality Project, Content moderation avoidance strategies, July 29, 2021

Instagram post, accessed Oct. 27, 2021

Facebook post, accessed Oct. 27, 2021

Tweet, accessed Oct. 27, 2021

Tweet, accessed Oct. 27, 2021

Instagram post, accessed Oct. 27, 2021

Tweet, accessed Oct. 27, 2021

Reddit post, accessed Oct. 27, 2021

Facebook post, accessed Oct. 27, 2021

Instagram post, accessed Oct. 27, 2021