Get PolitiFact in your inbox.

Attacks by Russia have battered the harvest of wheat and other grains in Ukraine. (Shutterstock)

If Your Time is short

-

The war in Ukraine will disrupt the supply of key commodities like wheat and sunflower seed oil.

-

Poorer nations that rely heavily on imports are most at risk.

-

Major exporting and wealthier nations like the U.S. are far less vulnerable.

-

A change in commodity prices has a limited impact on prices on the grocery store shelf.

There’s been a wave of social media posts recently warning of a looming food shortage in the U.S.. Some take the conspiratorial path.

"They aren’t predicting food shortages, they are planning them," said an April 3 claim on Facebook. Another points to a clip of President Joe Biden speaking and falsely claims it as proof of the same.

Other posts, such as one from commentator Dan Bongino, are more analytical. Bongino warned of what lies ahead when disruptions from the war in Ukraine collide with already rising food prices.

"A devastating food crisis is coming, ladies and gentlemen, and you darn well better be prepared," Bongino said April 12.

Bongino said he wasn’t trying to scare people, but his guidance was pointed.

"I can't warn you in strong enough terms," Bongino said. "Go out and get some extra stuff."

Bongino’s words connect with recent scenes. From toilet paper to canned tomatoes to loaves of bread, over the past couple of years, the pandemic has left many with fresh images of empty store shelves. Food inflation is palpable. The average price of food in March was up 10% from a year ago.

But as tough as inflation is on families, there is a difference between rising prices and goods being truly unavailable. The food researchers we reached said while Americans are likely to experience some problems tied to the war, poorer nations will bear the brunt of the impact.

"The U.S. food system has a good level of self-sufficiency, so currently, it is hard to imagine empty shelves in grocery stores," said Ohio State University agricultural economist Seungki Lee.

Food price drivers

To understand what might be coming to the U.S., we first need to understand what changes in the food economy are already at play.

Before the pandemic, American food prices changed little from month to month, sometimes rising or falling by a fraction of a percent. Then the virus hit. When infections caused meatpacking plants to close, the price of food eaten at home shot up 2.5% in one month.

Prices eased, but never returned to their pre-pandemic levels, and starting in December 2020, prices began a steady rise. In the past six months, Americans have seen an average increase of 1% each month.

Economists generally point to several drivers behind higher prices. Bad weather hurt harvests in South America and the midwest. Wages in the food sector went up. A host of supply-chain problems from packaging to transportation led to higher costs. And thanks to cash relief programs under the Trump and Biden administrations, people had money to spend, which tended to push prices up.

The rising cost of energy has lifted food prices for two reasons. With global supply lines, higher costs for moving goods pushes up food prices. But a rise in natural gas in particular plays a special role in agriculture. It is a key ingredient in making nitrogen-based fertilizer. The price of fertilizer in the U.S. essentially doubled between the summer of 2020 and the end of 2021.

Rising food bills, though, aren’t limited to the U.S. They have hit other major economies in Europe and Asia. To some extent, the core drivers lie outside the specific policies of any country.

All of that was in place before Russia attacked Ukraine.

The debate over the impact of the war in Ukraine

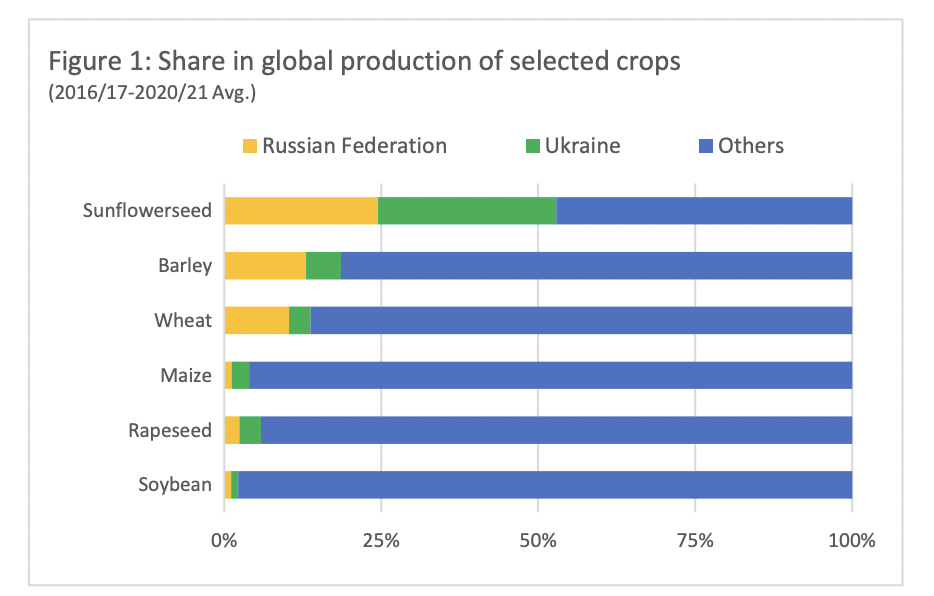

A key reason people are nervous is that both Ukraine and Russia are major exporters of agricultural products, particularly wheat, barley and sunflower seed oil.

Source: U.N.Food and Agriculture Organization report, March 25, 2022

Russia’s attack on Ukraine has battered Ukraine’s ability to plant, harvest and ship its goods. The season for harvesting wheat is fast approaching. The window to plant corn is closing. Russia can plant and harvest, but it faces international sanctions, which has raised uncertainty over the availability of its products in the global market. Anything that tightens supply leads to higher prices.

Researchers debate what this means for Americans.

With wheat, for example, the U.S. enjoys a cushion. It and Canada rank second and third, after Russia, as the largest global exporters of wheat. But, Lee said, reduced deliveries from Ukraine and Russia will push up global prices, and the U.S. will see some impact.

"Eventually, the cash price that farmers are seeing in the local market will follow global prices, and that will affect grocery store prices as well," Lee said.

How strong that upward pressure will be is an open question, because commodity prices and store prices follow their own paths.

Joseph Glauber at the International Food Policy Research Institute in Washington, D.C., emphasized that what you pay at the grocery store has a slender link to the price of the underlying raw material.

"If you look at wheat prices over the last 18 months, they’ve more than doubled," Glauber said. "But bread prices are up 5% to 6%."

Glauber says this also applies to goods like sunflower and other seed oils that the U.S. imports. He said these products play a limited role in the American household budget, however.

"Vegetable oil is overall a very small part of food inflation, here," Glauber said. "It’s about 3% of consumption."

Given the strength of the U.S. agricultural sector, the experts we reached downplayed worries of actual food shortages.

"The U.S. is a net exporter of agricultural products, so if things got dire, we can always cut back on exports," said Purdue University agricultural economist Jayson Lusk.

Members of the G-7 have said they want to avoid export restrictions, because they would fall heaviest on the countries least able to weather the turmoil.

Rising commodity prices due to the war in Ukraine are a matter of concern, but largely for developing economies. The U.N.’s World Food Program and Food and Agriculture Organization warn of painful consequences for people in Africa, the Middle East and parts of Asia.

The Food and Agriculture Organization said the war could bring "significant deterioration of global food security" in countries with lower incomes and greater reliance on imports.

Facing the unpredictable

While the war in Ukraine is dominating the food shortage discussion, agricultural economists underscored that global weather patterns remain the single most critical factor.

"Good weather and good yields are the main drivers of surpluses," said Lusk.

And more than Ukraine, Lusk is keeping an eye on other developments in major producing regions, including Brazil and Argentina for corn, and the U.S., Canada and Australia for wheat.

China can be a price driver unto itself. Lee said he’s watching how COVID-19 is hitting the country.

"If the China food system is severely damaged by the current wave of the pandemic, China would have to rely more on imports," Lee said. "They will aggressively jump into the global market and expand their purchases."

As it has before, that alone can push prices higher.

There is a chance that Biden’s plan to increase the use of corn-based ethanol could lead to higher corn prices, but Glauber said the impact of that policy shift is less significant than it might seem.

A limited number of gas stations have the mixing equipment to add more ethanol at the pump, Glauber said. And with the price of oil as high as it is, ethanol is a more competitive fuel, quite apart from Biden’s decision. Gasoline sellers already have an incentive to use the corn-based product as a low-cost octane booster to improve gasoline performance.

Our Sources

Facebook, post, April 3, 2022,

Instagram, Free Thought Project post, April 12, 2022

Facebook, post, March 26, 2022

Dan Bongino Show, A devastating food crisis is coming, April 12, 2022

White House, Remarks by President Biden in Press Conference - NATO headquarters, March 24, 2022

White House, Video: Biden Press Conference at NATO, March 24, 2022

USDA, World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates Report, April 8, 2022

IRI, CPG Supply Index, April 10, 2022

European Commision, European Food Prices Monitoring Tool, accessed April 15, 2022

Aaron Smith, The Story of Rising Fertilizer Prices, March 2, 2022

ARE Update, The Story of Rising Fertilizer Prices, February 2022

American University, Food Price Inflation is Endangering Global Food Security, Feb. 24, 2022

Purdue University, The Year of Food Price Inflation, Jan. 13, 2022

Reuters, Less rice for the same price: inflation bites Asia's food stalls, April 14, 2022

Wall Street Journal, Inflation Creeps Into Asia—‘My Salary Is the Same, but Everything Is More Expensive’, Feb. 21, 2022

International Food Policy and Research Institute, From bad to worse: How Russia-Ukraine war-related export restrictions exacerbate global food insecurity, April 13, 2022

Bureau of Labor Statistics, Food at home, accessed April 14, 2022

World Food Program, Food security implications of the Ukraine conflict, March 11, 2022

U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization, Food price index, accessed April 13, 2022

U.N.Food and Agriculture Organization, The importance of Ukraine and the Russian Federation for global agricultural markets and the risks associated with the current conflict, March 25, 2022

US Department of Agriculture, Foreign Agricultural Service - PSD database, accessed April 13, 2022

USDA Economic Research Service, Wheat Sector at a Glance, Feb. 2, 2022

Reuters, Ukraine war brings 'multi-year problem' for world food supply- U.N. agency, April 12, 2022

Farm Policy News, "It’s Going to be Real," President Biden on War-Related Food Shortages, March 25, 2022

Email exchange, Jayson Lusk, professor of agricultural economics, Purdue University, April 13, 2022

Interview, Joseph Glauber, senior research fellow, International Food Policy and Research Institute, April 15, 2022

Interview, Seungki Lee, assistant professor of agricultural economics, Ohio State University, April 14, 2022