Get bipartisan cooperation on the economy

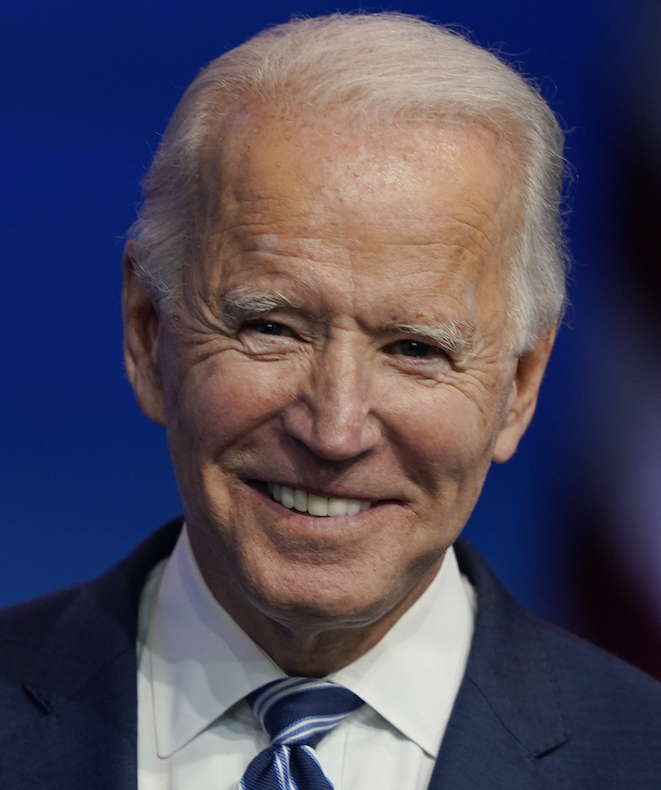

Joe Biden

"Look folks, we’re going to bring the Republicans and Democrats together, and deliver economic relief for working families, and schools, and businesses; I promise you."

Biden Promise Tracker

Compromise