Put US on a course to net-zero emissions by 2050.

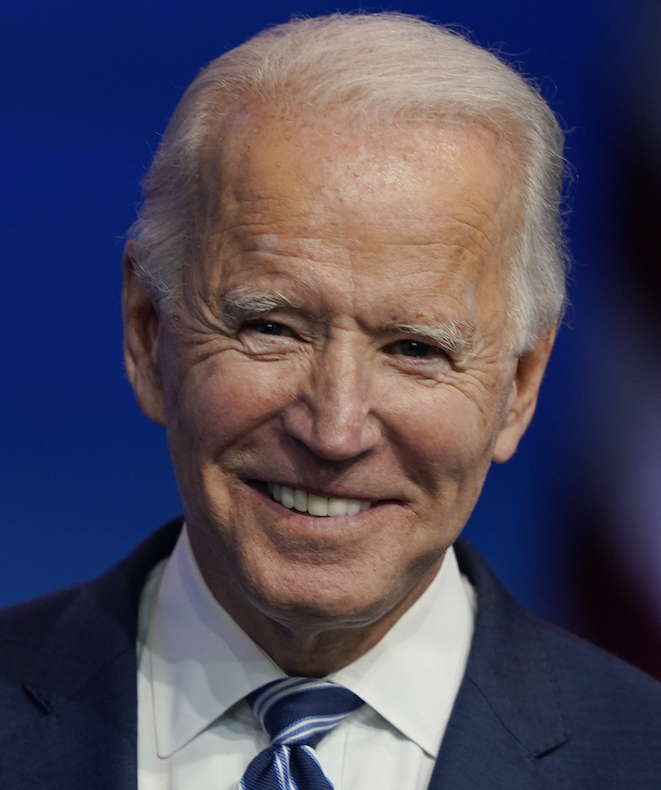

Joe Biden

"I will make massive, urgent investments at home that put the United States on track to have a clean energy economy with net-zero emissions by 2050."

Biden Promise Tracker

Promise Kept