Eliminate mandatory minimums for criminals

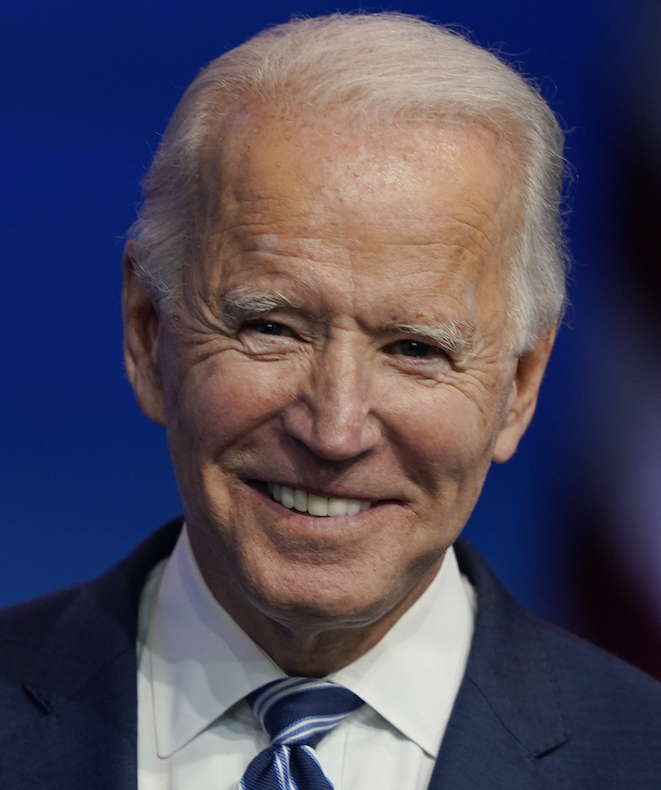

Joe Biden

"Biden supports an end to mandatory minimums. As president, he will work for the passage of legislation to repeal mandatory minimums at the federal level. And, he will give states incentives to repeal their mandatory minimums.

Biden Promise Tracker

In the Works