Update the Voting Rights Act

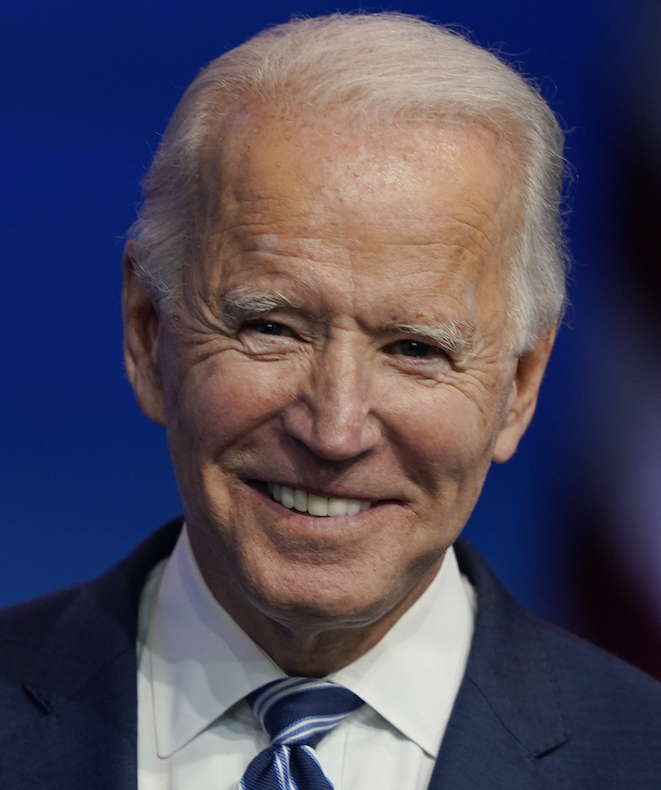

Joe Biden

"As President, Biden will strengthen our democracy by guaranteeing that every American’s vote is protected. He will start by passing the Voting Rights Advancement Act to update section 4 of the Voting Rights Act and develop a new process for pre-clearing election changes."

Biden Promise Tracker

Stalled