Rejoin Iran nuclear deal

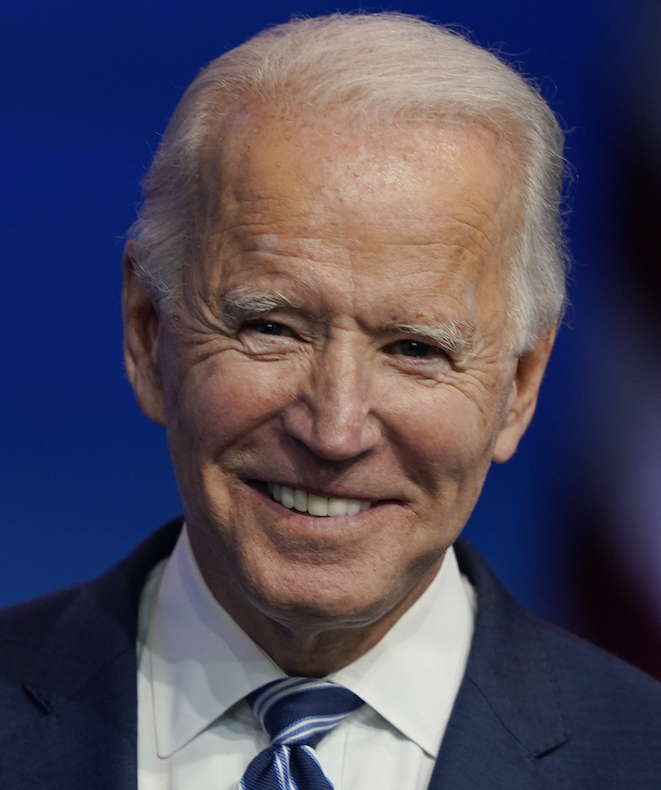

Joe Biden

"Tehran must return to strict compliance with the deal. If it does so, I would rejoin the agreement and use our renewed commitment to diplomacy to work with our allies to strengthen and extend it, while more effectively pushing back against Iran’s other destabilizing activities."

Biden Promise Tracker

Stalled