Guarantee 12 weeks paid family and medical leave

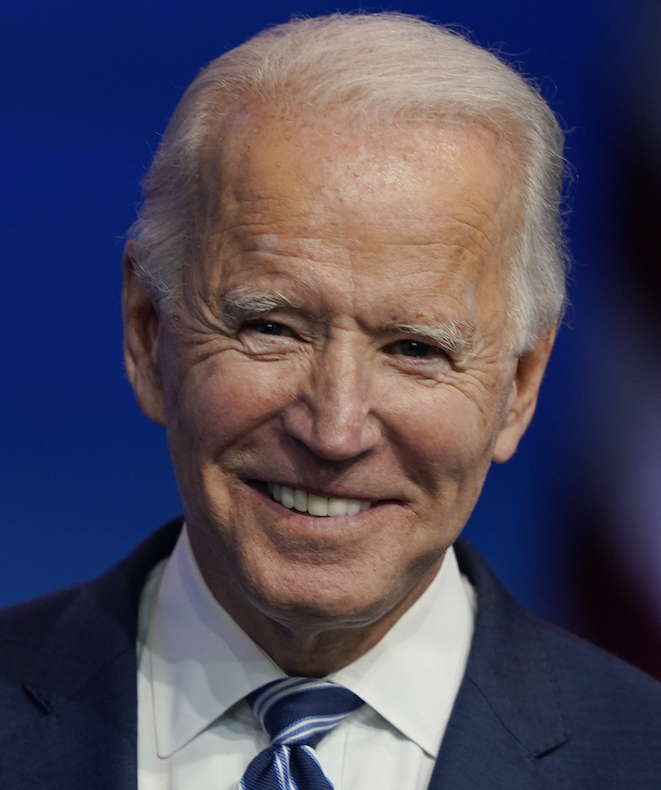

Joe Biden

"Biden will create a national paid family and medical leave program to give all workers up to 12 weeks of paid leave, based on the FAMILY Act."

Biden Promise Tracker

Stalled