Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

Peter Vegas of Boulder, Colo., takes a super-sized check after he was named the third of five weekly $1 million winners for being vaccinated against COVID-19 on June 18, 2021. (AP)

If Your Time is short

• Academic studies of early vaccine lotteries do provide reason for skepticism about how successful such programs have been.

• However, the studies so far have produced mixed findings, rather than unanimously negative ones. Two studies of Ohio’s lottery found a positive impact while two found no impact or a negative impact.

• Experts say that even in the most optimistic case, any gains from lotteries are likely to be small and would need to be supplemented by other efforts.

This summer, a wide range of states scrambled to create lotteries to incentivize citizens to get vaccinated for the coronavirus. In all, 26 states offered some type of incentive, with a majority using a lottery drawing, according to the National Governors Association.

On May 10, Ohio became the first in the nation to launch a weekly lottery, offering $1 million to randomly selected vaccine recipients over age 18 and four-year full scholarships to eligible participants under 18.

The plan was intended to jumpstart lagging vaccination rates in response to public health concerns that speedy and widespread delivery of vaccines was needed to most effectively curb the transmission of SARS-CoV-2, especially as more deadly variants emerged

In Georgia, however, Gov. Brian Kemp declined to follow suit.

"Lotteries haven’t worked in other states," Kemp said in a press conference on July 29. "Government mandates haven’t worked in other states," he said. "People at this point in the pandemic, they know how to deal with this. They know what they need to do. Some of them have been reluctant to do that."

Some states, including Louisiana, Washington, Maryland, and Michigan, have said they saw measurable increases in vaccine participation that they attribute in part to their states’ lotteries. Others have not. California’s Vax for a Win, which included vacation giveaways and tickets to Six Flags amusement parks, did not motivate residents to get vaccinated: The state experienced a 65% drop in the seven-day average of daily first doses. And in West Virginia, vaccination rates continued to decline after the lottery was announced.

Even in the states that say they saw some progress, the lottery might not have been the cause. Many factors could explain a raw-number increase in vaccinations, such as the infection and vaccination rates at the time the lottery was launched and the demographic profile of the population, said Robert Williams, a health sciences professor at the University of Lethbridge and a research coordinator for the Alberta Gambling Research Institute.

The happenstance timing of other events, such as the emergence of vaccine mandates by employers, can also complicate the task of figuring out whether lotteries worked.

As a result, a more reliable gauge is academic research that seeks to control for any complicating factors.

At least five academic studies have looked at this question, and their results have been mixed at best. Here’s a closer look. (Kemp’s office did not respond to an inquiry for this article.)

A sign advertising Ohio's COVID-19 mass vaccination clinic at Cleveland State University on May 25, 2021. (AP)

Studies of Ohio’s lottery

The Associated Press reported that Ohio’s lottery seemed to work initially. In the week after the "Vax-a-Million" program was announced, there was a 33% jump in the number of people in Ohio ages 16 and older who received their initial COVID-19 vaccine.

Still, the state’s vaccination rates remained well below figures from earlier in April and March. In fact, Ohio ended its five-week lottery in mid-June with Gov. Mike DeWine noting that the first-week jump in vaccines was followed by less-than-hoped-for results.

"Clearly the impact went down after that second week," DeWine told reporters.

No fewer than four studies — only one of them peer reviewed to date — have been published about Ohio’s experience.

Two papers found disappointing results.

• In a peer-reviewed paper published July 2 in the Journal of the American Medical Association, researchers from the Boston University School of Medicine used Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data to compare daily vaccination rates in Ohio with those nationally between April and June.

The authors wrote that the study did not find evidence that Ohio’s lottery was associated with increased rates of vaccination. But it also found that the vaccination rate in Ohio slowed less than the nationwide rate.

The Boston University researchers noted that Ohio’s lottery announcement coincided with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s May 10 expansion of vaccine eligibility to adolescents ages 12 to 15. It was a change that they suggested may have had an effect on adult vaccinations as well.

• A working paper released the same month, by researchers at Stanford University, compared full vaccination rates in Ohio to a composite of other states that most closely matched Ohio demographically.

"Contrary to our initial hypothesis, we found that after the lottery was announced, full vaccination rates in Ohio were slightly lower" than in the comparison group, said Lief Esbenshade, one of the paper’s authors.

The other two papers on the Ohio program did find a positive impact.

• One study, by economists at Oberlin College, compared first-dose vaccinations in counties along the Ohio border to those in neighboring counties in Indiana, Michigan, and Pennsylvania. The group found an increase in first-dose vaccinations, with larger increases in more populous counties.

• Another study, by researchers at the University of California-Santa Cruz, compared vaccinations in a way similar to the Stanford study, using a control group of states demographically similar to Ohio. It found that the program increased vaccination rates in Ohio by about 1.5%.

Methodological differences could explain some of the variations. For instance, the Stanford paper, which showed lower rates after the lottery began, looked at full vaccinations as opposed to initial vaccinations.

"It is possible that some of the differences between the papers can be explained by the Ohio lottery inducing a short term increase in first doses that did not convert into a sustained increase in full vaccination rates," Esbenshade said.

We found one other academic study of a lottery outside Ohio. It was by a team of researchers from the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Chicago; it looked at three vaccine lotteries in Philadelphia. The researchers concluded that there was a "limited return on even high-odds vaccine lotteries."

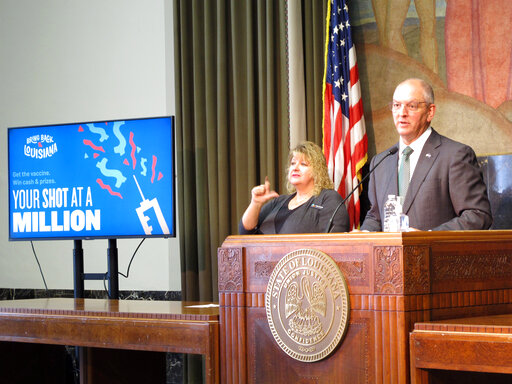

Louisiana Gov. John Bel Edwards speaks next to a sign promoting the state's coronavirus vaccine lottery on July 23, 2021, in Baton Rouge. (AP/Melinda Deslatte)

Lack of consensus

Researchers agreed that the mixed findings so far suggest uncertainty about whether vaccine lotteries work.

"There isn't any firm consensus," said Jeremy West, one of the co-authors of the University of California-Santa Cruz paper.

Future studies should help refine knowledge about what works and what doesn’t, said Allan J. Walkey, one of the authors of the Boston University paper. "I think that there will be more studies emerging shortly that will evaluate the effects of lotteries across multiple states and provide a more clear picture of effectiveness of lottery incentives on vaccine uptake," Walkey said.

Researchers told PolitiFact that if the costs are modest, lotteries might be helpful in boosting vaccination rates, but other tactics may be more cost-effective.

"Funds used for lotteries may potentially be better used to focus on vaccine misinformation, as well as outreach, engagement, and discourse with networks of people who are unvaccinated," Walkey said.

Meanwhile, policies that don’t involve a direct price tag at all, such as requiring vaccines for employees or students, may be more effective at this point in the pandemic, said Kevin Volpp, who co-authored the paper on the Philadelphia lotteries.

"It’s time for governors to use their power to require vaccination where possible and not rely on financial incentive programs or other ‘lighter touch’ strategies," Volpp said.

In recent weeks, Washington state has required all teachers to be vaccinated. California, the District of Columbia, Hawaii, Massachusetts, and Nevada are among the states that have required vaccinations for state employees, sometimes with a fallback option of weekly testing, while Maine has required health workers to be vaccinated.

At most, lotteries are only one part of the answer to increasing vaccination rates, researchers told PolitiFact.

"These incentive programs are not going to fully ‘solve’ vaccination hesitancy," West said. Even the most optimistic studies found a small positive impact, so it was "not that everyone in Ohio became vaccinated — although it's also the case that every vaccination obtained helps."

Our Sources

Atlanta Journal-Constitution, "Facing resign coronavirus cases, Kemp wants to stay the course," July 29, 2021

Greg Bluestein, tweet, July 29, 2021

Fox 5 Atlanta, State Sen. says Georgia can do more to get people vaccinated, July 30, 2021

New York Times, "These Are the U.S. states trying lotteries to increase COVID vaccinations," July 3, 2021

ABC 12 News Staff, "Sign-ups for Michigan COVID-19 vaccine lottery exceed 1 million", July 06, 2021

National Governors Association, "COVID-19 Vaccine Incentives," July 30, 2021

MIShotToWin, accessed Aug. 6, 2021

Office of the Governor, "Louisianans Vaccinated Against COVID-19 by July 31 Get a ‘Shot At A Million’ in $2.3 Million Lottery for Cash, Scholarship Prizes," June 17, 2021

Ohio Department of Health, "COVID-19 Update: Ohio Vax-a-Million, Kids Vaccination, Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation," May 13, 2021

Office of the Washington governor, "Inslee announces vaccination incentives," June 3, 2021

Washington state Department of Health, COVID-19 Data Dashboard, accessed August 10, 2021

San Jose Mercury News, "California vaccinations up as delta COVID surges--but is it enough?" August 4, 2021

MSN, "How West Virginia’s ‘Do it for Babydog’ vaccine lottery didn’t get the job done," August 4, 2021

THV11, "Arkansas officials admit incentives to get state vaccinated no longer working," June 29, 2021

Associated Press, "Ohio ends incentive lottery with mixed vaccination results," June 23, 2021

Email interview with Mike Nowlin, senior public relations manager for the Protect Michigan Commission, Aug. 6, 2021

Email interview with Franji Mayes, emergency communications consultant with Washington state, Aug, 6, 2021

Email interview with Christina Stephens, deputy chief of staff for communications for Louisiana Gov. John Bel Edwards, Aug. 9, 2021

Interview with Dan Tierney, press secretary for Mike DeWine, Aug. 10, 2021

Email interview with Robert Williams, health sciences professor and coordinator at the Alberta Gambling Research Institute, Aug. 12, 2021

Email interview with Allan J. Walkey, professor of pulmonary, allergy and critical care medicine at Boston University, Aug. 18, 2021

Email interview with Lief Esbenshade, doctoral candidate in the economics of education at the Stanford Graduate School of Education, Aug. 18, 2021

Email interview with Jeremy West, assistant professor of economics at the University of California-Santa Cruz, Aug. 18, 2021

Email interview with Sam Winter-Levy, doctoral student in politics at Princeton University, Aug. 18, 2021

Email interview with Kevin Volpp, director of the Center for Health Incentives and Behavioral Economics at the University of Pennsylvania, Aug. 18, 2021